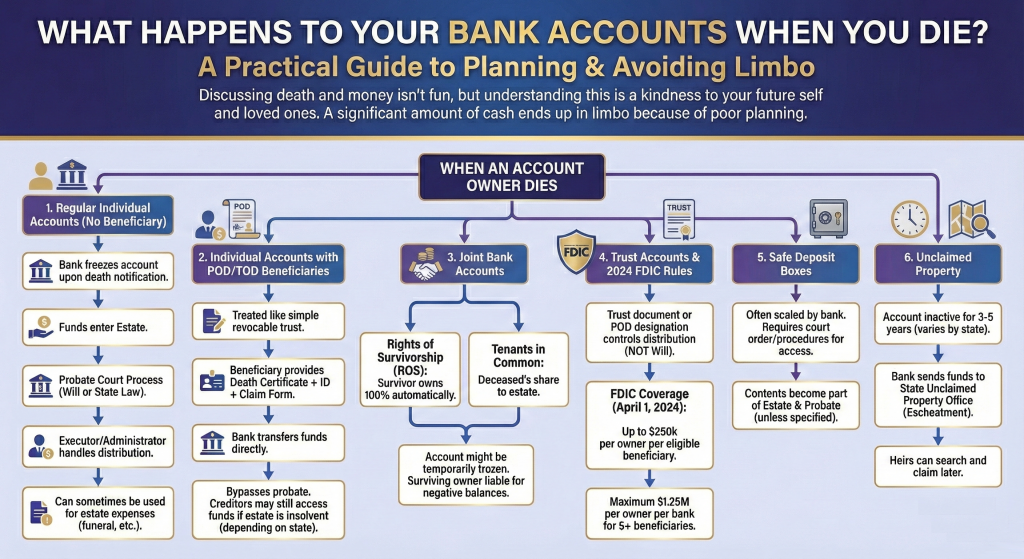

Talking about death and money in the same sentence is not anyone’s idea of fun. Still, if you have ever thought, “What actually happens to my bank accounts when I die?”, you are already ahead of the crowd. A lot of money quietly gets stuck in limbo every year because nobody set things up properly or nobody knew what to do when someone passed away.

The short version is this: banks do not just hand over your money to whoever shows up looking the saddest. How your accounts are handled after you die depends on how they are titled, whether you named beneficiaries, and what your local laws say. Get those pieces right while you are alive, and you make life much easier for the people you care about.

So, let us walk through what happens behind the scenes, how your loved ones actually get access to your money, and what you can do today so your cash does not end up as “mystery money” sitting with a bank or the state.

Big Picture: How Banks Handle Your Money After You Die

At a high level, your bank accounts can take one of a few different paths when you die. Which path they follow depends mostly on three things:

- How the account is titled (individual, joint, in a trust, business account, etc.)

- Whether you added any beneficiaries, such as payable on death (POD) or transfer on death (TOD) designations

- What your will and local laws say, especially if there are no beneficiaries or joint owners

For a basic individual account with no beneficiary, the bank will usually freeze the account once it learns of the death. The money then becomes part of the deceased person’s estate and is handled through probate. Probate is the court process where a judge confirms the will, appoints an executor, and oversees who gets what. If there is no will, state law decides who inherits.

If you have a joint account with rights of survivorship, the story is different. In that setup, when one person dies, the surviving owner usually becomes the sole owner of the account. Often, that happens without probate and the survivor can continue using the account after the bank sees a death certificate and updates its records.

If you named beneficiaries using POD or TOD designations, the money generally skips probate and is paid directly to the people you listed. The beneficiary typically has to show identification, a death certificate, and sign a few forms, then the bank either cuts a check or transfers the funds to them.

There is also deposit insurance in the background. In the United States, for example, FDIC insurance protects qualifying deposits at insured banks. When an account owner dies, coverage rules allow a short grace period so that the estate or beneficiaries have time to retitle or move money without losing coverage overnight.

Summary And Recommendations: The Short, Honest Answer

-

- When you die, your bank accounts either pass to a joint owner, go straight to a named beneficiary, become part of your estate and go through probate, or eventually get turned over to the state as unclaimed property, so if you want your money to reach the right people smoothly, you should use beneficiaries, understand your joint accounts, keep a basic estate plan, and make sure someone knows where you bank.

If you want the least possible chaos for your family, here is a practical checklist you can work through:

- Add POD or TOD beneficiaries where appropriate. For key checking and savings accounts, consider adding payable on death or transfer on death beneficiaries so the bank can pay them directly without probate.

- Make sure your joint accounts are set up the way you think they are. Confirm whether they truly have rights of survivorship and that the person on the account is the person you actually want to inherit everything in that account.

- Keep a simple, up to date will. This covers individual accounts without beneficiaries and any other assets that do not have their own beneficiary designations.

- Stay within deposit insurance limits. If you have large cash balances, spread them across banks or account types as needed so that you are not accidentally leaving uninsured cash behind.

- Let at least one trusted person know where you bank. A short list of your banks and credit unions can save your executor a ton of time and help prevent accounts from being forgotten and eventually treated as unclaimed property.

- Tell your family where to look for “lost” money. Teach them about official unclaimed property search sites offered by governments so they know where to search if something is missed.

Detailed Analysis: What Happens To Different Types Of Accounts

Now let us dig into how this plays out for the main account types you are likely to have.

1. Individual checking and savings accounts with no beneficiary

- Once the bank is notified of your death, it may freeze the account to prevent new withdrawals or changes.

- The balance typically becomes part of your estate and is managed by your executor or court appointed administrator.

- The executor uses that money to pay final expenses, taxes, and debts, and then whatever is left is distributed to heirs under your will or under default state law if there is no will.

- Because everything passes through probate, the process can take months or even longer, and there may be legal and court fees.

2. Individual accounts with POD or TOD beneficiaries

- The account is still in your name while you are alive. The beneficiary has no rights while you are living.

- After your death, the beneficiary shows the bank a certified death certificate and identification and signs whatever claim forms the bank requires.

- The bank then pays the balance directly to the beneficiary, often faster and with less cost than a full probate process.

- These accounts usually are not controlled by your will. If your will and your beneficiary designations conflict, the bank follows the beneficiary form.

3. Joint accounts

Joint accounts can be great or they can be a huge source of confusion, depending on how they were set up and what everyone expects.

- Joint with rights of survivorship. This is very common for married couples. When one owner dies, the surviving owner automatically becomes the only owner of the account and can usually continue using it after providing a death certificate.

- Joint without rights of survivorship. In some setups, each owner has a share of the account. When one owner dies, that person’s share may go into their estate and pass according to their will or state law rather than going entirely to the surviving account holder.

- Debt still matters. If the joint account is overdrawn or tied to a line of credit, the surviving co owner may still be responsible for that debt even after the other person dies.

4. Trust accounts

- Some people place bank accounts into a revocable living trust or name the trust as a beneficiary.

- In that case, the terms of the trust control who gets the money and on what schedule, rather than the will.

- Trust accounts can help avoid probate, add privacy, and give more control over timing and conditions, especially for minor children or complex family situations.

5. Business accounts

- If you have a sole proprietorship, the business account is usually treated like your personal account and becomes part of your estate.

- If the account belongs to a separate legal entity, such as an LLC or corporation, the business may continue to operate and the ownership of the business itself passes according to your operating agreement, bylaws, will, or buy sell agreements.

6. What happens if nobody claims the money

- If an account sits untouched for several years, banks are generally required by law to mark it as dormant and eventually turn the funds over to the state as unclaimed property.

- Heirs can often claim that money later from the state, but it involves paperwork and proof of relationship, and it only happens if someone knows to go looking.

How Different Setups Help Or Hurt The People You Leave Behind

This is the part where we look at the practical tradeoffs. Not in a law school way, but in a “what is this like for my spouse, kids, or whoever is cleaning up my paperwork” way.

Leaving accounts as simple individual accounts with no beneficiary

- Upside: During your life, everything is straightforward. The account is fully under your control and you do not have to coordinate anything with other people.

- Downside: After your death, your loved ones may have to go through probate before they can access the money. That can take time and cost money, which is not ideal if they need cash for funeral costs, living expenses, or urgent bills.

- When it can still be fine: If balances are small or your estate is very simple and your state offers a quick, low cost probate option, this setup may not cause major problems.

Using POD or TOD beneficiaries on key accounts

- Upside: Usually the fastest way to get money into the hands of the people who need it. It also keeps that account out of probate, which can simplify things for your executor.

- Downside: If you forget to update beneficiaries after big life events, such as divorce, remarriage, or the birth of a child, your money might go to someone you no longer intend to benefit.

- Best use: Emergency cash accounts, everyday checking, or savings you know you want to send directly to specific people.

Relying heavily on joint accounts

- Upside: Your partner or co owner can keep paying bills if you die first. The transition at the bank level is often relatively quick once they bring in a death certificate.

- Downside: You are giving that joint owner full access during your life. If they overspend, have creditors, or get divorced, that can affect your money too.

- Best use: Long term, stable relationships where finances are genuinely shared and you both are comfortable with that level of access.

Creating a living trust and using trust accounts

- Upside: Can avoid probate for those assets, adds privacy, and lets you set conditions or timelines for distributions. It can be especially useful in blended families, for minor children, or if you worry about a beneficiary handling a large lump sum.

- Downside: More complex and more expensive to set up. You also have to remember to retitle accounts into the trust or name it as a beneficiary. Forgetting that step is like buying a fancy organizer and never putting anything in it.

- Best use: People with larger estates, complicated family dynamics, or specific wishes that a simple beneficiary form cannot handle well.

Doing nothing and hoping it sorts itself out

- Upside: From your point of view while alive, it feels easier because you never have to make decisions or fill out extra forms.

- Downside: You are basically outsourcing the complexity to your future widow, partner, kids, or friends. They will have to track down your accounts, deal with probate, and maybe even chase unclaimed property years later.

- Best use: Honestly, this is the “I did not get around to it” option, not a strategy.

Planning Ahead: Turning A Tough Topic Into A Simple To-Do List

This section is where we zoom out from the account mechanics and talk about how to turn all of this into a manageable weekend project instead of something that lives forever on your “someday” list.

Make a one page “money map”

- List your banks and credit unions, the kinds of accounts you have at each, and roughly what they are for (bills, savings, emergency fund, business, etc.).

- Keep this somewhere safe but findable, such as with your will or in a secure digital vault.

Align your accounts with your bigger life plan

- If your goal is for your partner to be able to keep the lights on without legal drama, make sure at least one account they can access quickly will have enough to handle a few months of expenses.

- If your concern is fairness among children, double check that your beneficiary setup actually matches what you think is fair, not just what you did ten years ago.

Keep the emotional side in mind

- When someone dies, the people left behind are juggling grief, paperwork, and bills at the same time. The more clearly your accounts are set up, the fewer painful decisions they have to make when they are already overwhelmed.

- Even a short conversation like, “If anything ever happens to me, here is who you call and where the money is” can reduce a huge amount of stress later.

Check in every few years

- Any time you have a major life change, such as marriage, divorce, kids, buying a home, or starting a business, that is a good moment to revisit your bank account setup.

- Beneficiary forms, joint accounts, and trusts are not “set it and forget it” items. They are more like a car. They run for a while on their own, but every so often you need to pop the hood.

Quick Recap & Where to Learn More

Here is the short version so you do not have to reread the entire article.

- Your accounts follow the path you set up while you are alive. Money can go to a joint owner, to named beneficiaries, into your estate for probate, or, if nobody claims it and it sits long enough, into your state’s unclaimed property system.

- Beneficiaries and joint ownership can speed things up. Payable on death and transfer on death designations, along with properly set up joint accounts, usually allow money to reach your loved ones faster and with less court involvement.

- Your will does not control everything by default. Accounts with beneficiaries or joint owners generally follow those designations first, and the will only controls what does not already have its own instructions.

- Insurance and protection still matter after you die. Deposit insurance rules continue to protect eligible balances for a period of time while the estate or beneficiaries retitle accounts and move funds.

- Silence creates work for the people you care about. If nobody knows where you bank or how accounts are titled, your heirs may end up searching for accounts, dealing with delays, or filing unclaimed property claims years later.

- A bit of planning now goes a long way. A simple combination of a basic will, up to date beneficiary forms, clearly structured joint or trust accounts, and a short “here is where everything is” note can prevent most of the financial chaos that tends to show up after a death.

If you want to read more or double check details, these are good starting points:

- FDIC: Your Insured Deposits explains how deposit insurance works and what happens when an account owner dies.

- FDIC EDIE Calculator lets you plug in your own accounts to see how much coverage you have under current rules.

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) Ask CFPB has plain language answers on joint accounts, beneficiaries, and estate issues.

- USA.gov Unclaimed Money explains how to search for forgotten or unclaimed accounts in the United States.

- National Association of Unclaimed Property Administrators (NAUPA) links to official state unclaimed property sites where heirs can search for old accounts.

The topic can feel a little dark, but the actual task is pretty doable. The good news is that you do not have to fix everything at once. Start by picking one bank, checking how that account is set up, and making sure someone you trust knows it exists. That single step already makes life easier for the people who care about you.

Leave a Reply